Patent rights have been a key driver of U.S. prosperity since they were enshrined in our Constitution more than 230 years ago. America’s status as the world’s strongest economy, our role in pioneering new technologies, and our continued national security all rely on patent laws that promote innovation by guaranteeing inventors an exclusive right to their creations. The positive impact of our patent system helps the U.S. biopharma industry introduce more than half of the world’s new drugs. Despite this, the biopharma industry’s use of patents is frequently singled out and attacked with misleading claims.

For example, anti-patent activists have repeatedly made unfounded and highly questionable assertions that pharmaceutical companies unfairly “extend” patents in order to prolong market exclusivity and prevent generic competition. Not only is it impossible to extend a patent in this way, but an analysis of how the patent system is used in this industry shows that biopharma companies usually do not get even close to the length of a full patent term — 20 years — before they face generic competition. Nor does the number of patents covering a particular drug make it too hard for generic competition to enter the market, another claim frequently made by these activists.

A 2024 report issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) makes these points. The report was requested in 2022 by Senator Thom Tillis (R-NC) — the lead Republican of the Senate Intellectual Property Subcommittee — who wanted an independent analysis of the claims being made by these anti-patent activists.

To conduct its study, the USPTO reviewed 25 new drug applications (NDAs), 13 of which had generic products enter the market during the period that the USPTO studied. It reported the number of patents each product had listed in the FDA’s “Orange Book,” which identifies “patents . . . that may protect a brand-name drug from generic competition,” according to the Congressional Research Service. It then analyzed whether there was a relationship between the number of patents on the drug and the amount of time before the drug’s generic equivalent entered the market.

The USPTO ultimately found that there is no correlation between the number of patents on a drug and the timing of generic entry. It determined that abandoned and pending patent applications, as well as “follow-on” patents, have no impact on exclusivity. It also clarified that there is nothing unusual about drug companies’ use of multiple patents to protect different aspects of a single product, noting that this is common practice for complex technologies in any sector.

Below, we detail each of the study’s key takeaways, as well as the common anti-patent myths that they refute.

- Simply Counting Granted Patents Does Not Provide a Meaningful Assessment of the Patent Landscape, nor When Generic Drugs Will Enter the Market

The USPTO’s analysis found that looking at the number of granted patents alone that are associated with a given product provided no meaningful insight into the scope of the product’s patent protection, its period of market exclusivity, or the timeline for generic competition. The report states:

“The results illustrate that simply quantifying raw numbers of patents and exclusivities is an imprecise way to measure the intellectual property landscape of a drug product because not every patent or exclusivity has the same scope . . . [S]imple counts of patents can be misleading when every patent is counted equally, because the number of patents does not provide a clear picture of the landscape without a review of the scope of the claims in each patent.” (p. 57)

This finding directly contradicts frequent claims made by activist groups such as the Initiative for Medicines, Access, and Knowledge (I-MAK), who cite the large number of patents protecting certain medications as evidence that drug companies are attempting to misuse patents to obtain an excessive period of market exclusivity.

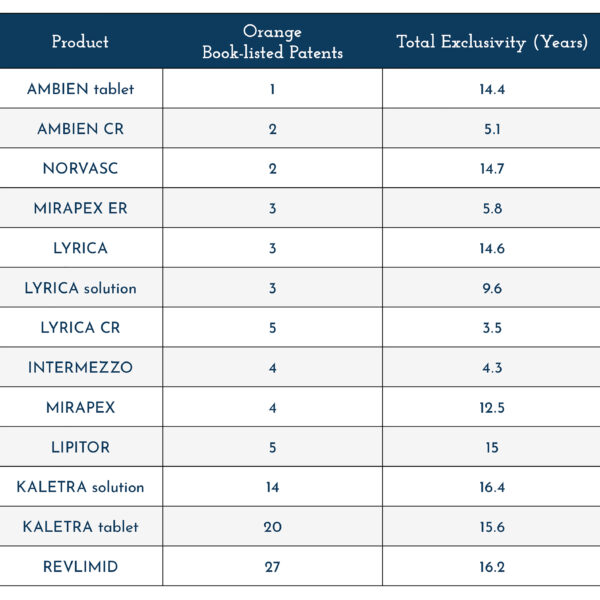

The USPTO also found that the longest period of market exclusivity among the 13 NDAs it studied was only 16.4 years, and the average length of exclusivity was just 11.4 years. None of the 13 products had market exclusivity lasting the equivalent of a full patent term of 20 years, notwithstanding being associated with between one to 27 patents in the Orange Book. This supports the fact that drugmakers do not have the ability to extend the market exclusivity for their products by filing additional patents.

Overall, the USPTO report established that there was no clear correlation between the number of Orange Book patents associated with a drug and the timeline for generic competition.

During C4IP’s briefing on the topic, Emily Michiko Morris, associate director of the Center for Intellectual Property Law & Technology at the University of Akron School of Law, explained this further, saying:

“The studies that are out there all tend to prove that the number of drugs, or the number of patents on a given drug, do not have an effect on when generics enter the market or when biosimilars enter the market. There are a number of studies that Jamie [Simpson, C4IP chief policy officer and counsel] referred to that say, ‘Hey look, for the last 30-plus years, the time between when a brand-name drug enters the market and when a generic version enters the market has not really changed.’ And if anything, it’s decreased over time. In my research, it’s about 13 years — somewhere between 11 and 13 years — and it’s decreasing, if anything . . . And the PTO’s data reflect this.“

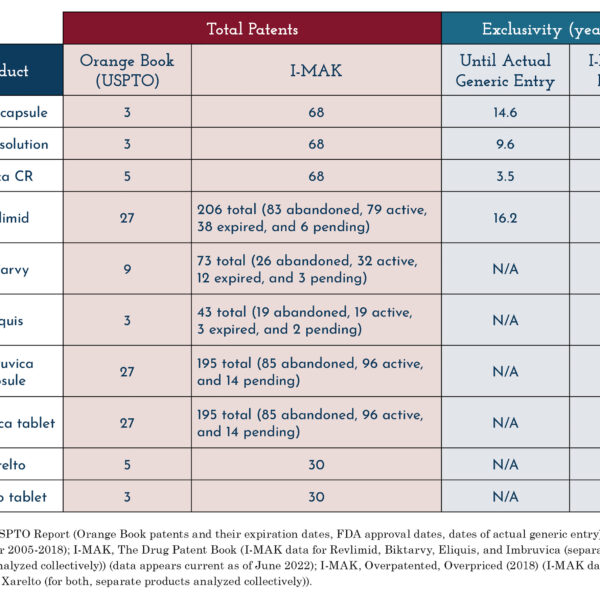

One reason that patent count alone is not indicative of the length of exclusivity for a given drug is that not all patents, but “only patents listed in the Orange Book can affect the timing of FDA approval of a generic drug. Patents that are not listed in the Orange Book do not impact the timing of FDA approval of a generic drug application” (USPTO Report, p. 13). Consequently, data that combines Orange Book and non-Orange Book patents, such as that compiled by I-MAK, paints a misleading and inaccurate picture of how patent protections relate to generic entry into a market.

Other data published by I-MAK has also been called into question. Past reports from the organization claiming that patents are impeding access to drugs were directly contradicted by statistics from the FDA’s Orange Book. Unexplained discrepancies between I-MAK’s data and official figures have also previously prompted scrutiny from lawmakers.

- Follow-On Patents Do Not “Extend” Earlier Patents and Do Not Block the Introduction of Generics

The USPTO report explained that “follow-on” patents, which are patents filed for improvements to an existing product, do not extend a drug’s period of exclusivity or prevent generic competitors from entering the market. It states:

“[T]his study identifies several examples of such follow-on patents . . . In some of these examples, the data indicates that a generic competitor drug was approved and launched, while later patents directed to follow-on innovation and listed in the Orange Book were still in force. For example, a generic competitor launched a competing product to LIPITOR, before all the patents expired.” (p. 5)

“In other cases, later patents may have claims directed only to specific aspects of the [innovator company’s] product, and may not block a generic from launching a competing product once the earlier patents have expired.” (p. 6)

The USPTO’s findings reinforce the fact that follow-on patents only protect specific improvements to a product, such as a new formulation of a drug that allows it to be administered in a different way. Once the original patents on the product expire, competitors are free to copy that version of the product; they simply cannot copy the later improvement. Follow-on patents do not alter the length of a product’s original patents.

This is contrary to a common argument made by anti-patent activists, who claim that drugmakers file follow-on patents as a means of extending their products’ exclusivity. This alleged practice, commonly referred to as “evergreening,” is not correct.

- Only Issued Patents, Not Pending or Abandoned Applications, Provide Exclusivity

The USPTO report affirmed that pending or abandoned patent applications do not affect market exclusivity. This is because patent rights are not enforceable until the patent is actually issued. The report spells this out, stating:

“The study includes only granted patents and does not include pending or abandoned patent applications. Abandoned applications do not result in granted patents, and thus, do not pose a barrier to competition. The study also does not discuss pending patent applications, because they are not listable in the Orange Book and may never become patents, and if no patent is granted, there is no enforceable right. As a result, the total of all abandoned and pending applications is not a meaningful metric.” (p. 13)

In the past, activist groups have misleadingly implied that pending or abandoned patent applications can affect market exclusivity. For instance, the top-line patent counts provided by I-MAK erroneously list abandoned and pending patent applications, purporting to show a relationship between these applications and the length of the drug’s exclusivity period.

The USPTO report’s clarification that only issued patents provide exclusivity is yet another reminder of the flaws in I-MAK’s data and methodology.

- Many Innovative Products, Not Only Pharmaceuticals, Are Covered by Multiple Patents, and Top Patentees Are Concentrated in Tech, Not Pharma

A fourth important clarification in the USPTO report is that the practice of filing multiple patents to protect distinct innovations within a single product is common and not limited to the pharmaceutical sector. The report states:

“With respect to multiple patents that cover a single product, multiple patents associated with a single marketed product are not unique to the pharmaceutical industry and are a common practice in many innovative industries, especially for complex products.” (p. 58)

Critics of patent rights often point to drug products protected by numerous patents as evidence that pharmaceutical companies “game” the patent system. But as the report confirms, there is nothing nefarious or even unusual about products that rely on multiple patented components. Rather, this is evidence that the patent system is doing its job in helping translate innovators’ smaller, incremental discoveries into complex products that benefit the public.

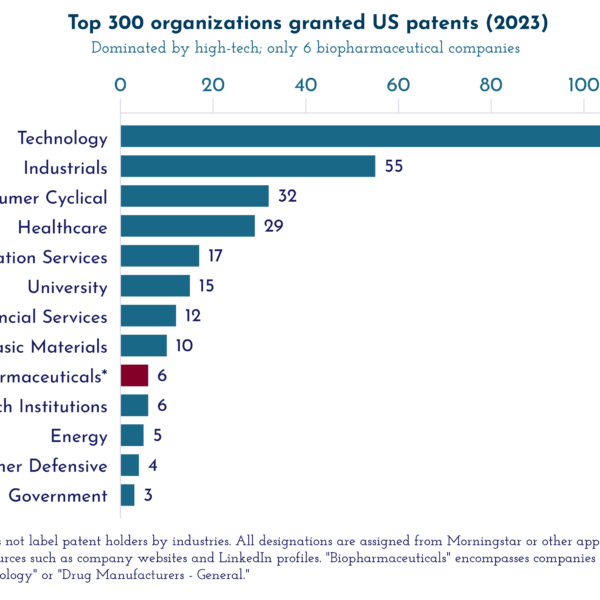

In fact, despite accusations of “patent gaming” in the pharmaceutical sector, the tech sector files far more patents than drug companies. The tech sector dominates the Intellectual Property Owners’ Association (IPO) 2023 annual report of the top 300 patentees in the United States, with publicly traded tech companies comprising nearly 100 entities on the list. In contrast, the list includes only six biopharma companies (2% of the total).

The total number of patents (9,036) granted just to the top patentee, Samsung Electronics, is over three times the total number of patents granted to the biopharma companies on the list (2,748).

Conclusion

The USPTO’s study refutes the common narrative that biopharma companies abuse patent protections to extend market exclusivity and reduce generic competition. It reveals that contrary to misleading statistics published by anti-patent organizations such as I-MAK, pending and abandoned patent applications, “follow-on” patents, and granted patents not listed in the FDA’s Orange Book do not affect the timing of generic drug market entry.

Despite those organizations’ claims, the USPTO demonstrates that there is no clear correlation between the number of patents filed on a drug and the duration of its market exclusivity, with the average period of drug exclusivity being significantly shorter than the 20-year duration of a patent term. As analysis of the data published by IPO separately shows, even though allegations of patent ‘gaming’ often target drug developers, the tech sector dominates the list of top U.S. patent-holding companies — not biopharma.

As Sen. Tillis stated in one of his letters to the USPTO, policy decisions regarding patents and drug development must be “based on accurate, reliable, and replicable facts and evidence.” The comprehensive evidence gathered by the USPTO’s study makes clear how misleading some of the information Congress is given about patents and drug prices is. Instead of providing a reliable basis on which to legislate, this constellation of misinformation points the way to lowering innovation to cure and treat diseases in the future, reducing everyone’s access to the next generation of lifesaving medicines.